Does "Sabbaton" in

Luke 18:12 really mean "week"?

For the 2nd Edition of the Scroll of Biblical Chronology and Prophecy

Note: important update in Appendix II.

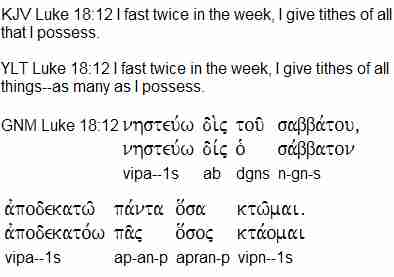

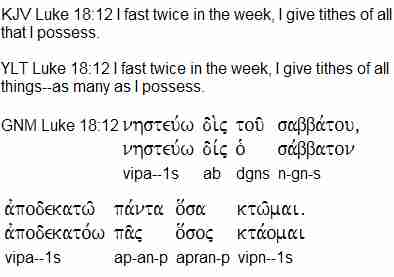

Our English translations of Luke 18:12 say, "I fast twice a week". However, the word for "Sabbath" occurs in the Greek text where the translators have written "week":

This text

represents the Hebrew

.

The genitive definite article before Sabbath is represented by the lamed

and the vowel under the lamed. The original Hebrew

uttered by the Pharisee (and Yeshua) is clear enough in that language, "I

fast twice with respect to the Sabbath", which is the same as similar pious usage in other

Jewish sources. See my annotated

Chart of the Week for these usages.

The point of reckoning time with reference to the Sabbath was to give a pious

notice of the Sabbath. If Sabbath meant only "week" then there

is no reason that such usage would have supplanted the normal usage, "I fast

twice a seven" which in Hebrew would be Shavua, a derivative of the

number seven meaning "week". Actually, it still has the sense of "seven".

The before mentioned chart of the week will show that "I fast twice a Shavua"

would be the normal mode of expression.

.

The genitive definite article before Sabbath is represented by the lamed

and the vowel under the lamed. The original Hebrew

uttered by the Pharisee (and Yeshua) is clear enough in that language, "I

fast twice with respect to the Sabbath", which is the same as similar pious usage in other

Jewish sources. See my annotated

Chart of the Week for these usages.

The point of reckoning time with reference to the Sabbath was to give a pious

notice of the Sabbath. If Sabbath meant only "week" then there

is no reason that such usage would have supplanted the normal usage, "I fast

twice a seven" which in Hebrew would be Shavua, a derivative of the

number seven meaning "week". Actually, it still has the sense of "seven".

The before mentioned chart of the week will show that "I fast twice a Shavua"

would be the normal mode of expression.

What

remains then is to explain how the Greek text of Luke got the way it did.

Starting from the Hebrew above that is not hard to see.

standing without comprehension of the context of practices of the Pharisees can

easily be either, "I fast twice to the sabbath" or "I fast twice the sabbath"

i.e. on it. While we know now that the Pharisees fasted on Mondays

and Thursdays, this was not a fact known so widely to Gentile scribes.

Luke's first MSS could easily have read "to the sabbath" in the first century

i.e.

standing without comprehension of the context of practices of the Pharisees can

easily be either, "I fast twice to the sabbath" or "I fast twice the sabbath"

i.e. on it. While we know now that the Pharisees fasted on Mondays

and Thursdays, this was not a fact known so widely to Gentile scribes.

Luke's first MSS could easily have read "to the sabbath" in the first century

i.e.

![]() ,

and then have been altered by some scribe in the second century to

,

and then have been altered by some scribe in the second century to

![]() thinking

that the text meant "I fast twice on the Sabbath". The scribal

practices of Christian scribes were no where near as exacting as Jewish scribes.

In fact, it was regarded as allowable to improve the text in this period.

We have early MSS from the second century when compared with fourth century MSS

that show these tendencies. However, for this section of Luke we

have no early MSS. So the change has gone undetected.

Indeed, the text of the book of Acts is about 10% longer in the Byzantine MSS

than in the older MSS. This is because scribes tended to conflate

various readings, which means they put both into the text.

Differences in case endings and spellings were not uncommon either, and here I

am only proposing a case ending corruption, and a very easy one to make at that.

"Too" sounds very similar to "toe".

thinking

that the text meant "I fast twice on the Sabbath". The scribal

practices of Christian scribes were no where near as exacting as Jewish scribes.

In fact, it was regarded as allowable to improve the text in this period.

We have early MSS from the second century when compared with fourth century MSS

that show these tendencies. However, for this section of Luke we

have no early MSS. So the change has gone undetected.

Indeed, the text of the book of Acts is about 10% longer in the Byzantine MSS

than in the older MSS. This is because scribes tended to conflate

various readings, which means they put both into the text.

Differences in case endings and spellings were not uncommon either, and here I

am only proposing a case ending corruption, and a very easy one to make at that.

"Too" sounds very similar to "toe".

For the sake of argument, I will mention Acts 15:24 where the late western text adds, "saying, Ye must be circumcised, and keep the law: to whom we gave no such commandment:". These anti-Torah words are not in the earliest MSS, and have been correctly removed from translations like the New American Standard Bible. However, would anyone in the 1700's know this? Of course not, since the older MSS were only discovered later. But since we have no old MSS of Luke, we have no way of knowing for sure. Could such a change have been motivated by the interpretation of 'week' for 'sabbaton' in the resurrection passages? How does a mistake in a few MSS get into all of the current MSS? Well, we say that when the Romans purged most of the MSS that the one with the mistake is the one that survived, and then this one became the exemplar for the MSS that followed. God knew that corruptions were bound to occur. It's human nature, so that's why He gave us four gospels and not just one.

One odd text is not sufficient reason to introduce a new definition to "sabbaton" for the first century period. A lexical meaning should be established by many witnesses and not just one text. In fact, three witnesses ought to be required where an immediate contradiction would occur if said meaning did not apply. However, "I fast twice the sabbath" implies no immediate contradiction. O.k., it only contradicts the assumption that Yeshua was talking about the Pharisees that fasted on Monday's and Thursdays. But even if he was, the text only becomes an anomaly and not definitive proof that "Sabbath" meant week. If "Sabbath" meant week, plain and simple, then there is no apparent reason for the change from using the common word for week, i.e. seven or Shavua, and there is every reason to think that counting "to" the Sabbath was a pious usage, which exactly fits the character of some Pharisees. Perhaps there was some unknown class of Essene type Pharisee that skipped two meals on the Sabbath. (This has been suggested in some traditional sources). There are just too many unknowns to go depending on one witness for the meaning "week" when the meaning "sabbath" gives sense also.

But even if it be admitted

that "sabbaton" means "week" in this one passage (and I do not agree that it

does), it would be insufficient data to take the phrase "one [day] of the

Sabbaths" in the resurrection passages and apply it there. This is

because the construction of the phrase in Greek is based on the normal usage for

the Sabbath day, "day of the Sabbaths", except that the word "one" has been

tacked on the front, and the word "day" dropped because it is implied by the

gender of "one". This is sufficient from the Greek point of view to

prevent

![]() from

meaning anything but a regular sabbath with the word "one" or "first" tacked on

the front, which is explained by Lev. 23:15. And in fact, the whole

phrase is a pure Hebraism for

from

meaning anything but a regular sabbath with the word "one" or "first" tacked on

the front, which is explained by Lev. 23:15. And in fact, the whole

phrase is a pure Hebraism for

![]() which was used to designate the first Sabbath after Passover as distinct from

the first Sabbath in Lev. 23:11, which was called

which was used to designate the first Sabbath after Passover as distinct from

the first Sabbath in Lev. 23:11, which was called

![]() to keep it distinct from the first Sabbath after Passover.

to keep it distinct from the first Sabbath after Passover.

The rest of the matter is secured by the overall chronology and the many details that only make sense with the resurrection on the Sabbath. It would be quite unparsimonious to use one text to overrule the host of chronological details that support it.

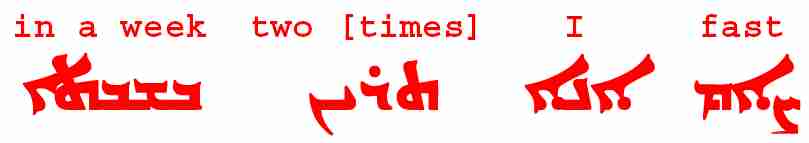

Appendix I: The Syriac Luke 18:12. In the extraction below from www.peshitta.org the Syriac word below "in a week" is "unto the Sabbath": "I fast two times on toward the Sabbath". This shows a pious usage of "sabbath" in relation to a biweekly fast, but it is still not an example of counting days to the Sabbath.

Appendix II: Updated 10/22/2009

Sabbath: To Feast or to Fast?*

[by Eliezer Segal, University of Calgary]

Our familiar Shabbat has so much to do with eating and drinking that we might

well feel bewildered to hear that many ancient writers believed that Jews

celebrated their holy day by abstaining from food.

According to the first-century Roman historian Pompeius Trogus, Moses instituted

the Sabbath as a fast day in order to commemorate the Israelites' seven days of

deprivation when they trekked through the Arabian desert on their way to Mount

Sinai. Augustus Caesar once wrote to Tiberius "Not even a Jew fasts so

scrupulously on his Sabbaths as I have today."

The satirist Petronius speculated about the dire fates in store for

uncircumcised Jews who, as he wryly put it, would be exiled by their intolerant

coreligionists to Greek cities where they would be unable to observe their

Sabbath fasts. And Martial tried to insult a correspondent by accusing him of

having a breath that smelled "worse than one of those Sabbath-fasting Jewish

women."

Our first reaction is to marvel at how so many writers, including some of the

most respected names in Greek and Latin letters, could have gotten their facts

so absurdly wrong. If anything, Shabbat is a day of overeating, during which it

is mandatory to partake of at least three meals. Except in very rare cases,

fasting is strictly prohibited.

Many scholars dismissed this stubborn inaccuracy as yet another ignorant

stereotype about Jews that was copied indiscriminately from author to author in

spite of the fact that it had no basis in reality.

However, if we examine the talmudic sources more carefully, we discover that the

attitudes of the ancient Jewish sages towards eating on the Sabbath were more

ambivalent than might be suggested by our current practice.

Take for example the case of Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus who insisted on drawing

out his classes for the entire day, and expressed disdain at the faint-hearted

students who snuck away to join their family repasts.

Rabbi Yosé ben Zimra went so far as to declare that Jews who fasted on Shabbat

were assured of the cancellation of any negative decrees that had been issued

against them by the heavenly court.

It would appear therefore that, alongside the mainstream view that regarded

Shabbat as a day of physical as well as spiritual delight, there existed a

significant minority of sages who wanted it to be a day of exclusively spiritual

contemplation, on which physical desires should be minimized or suppressed.

It is likely that at the root of this ancient dispute lay divergent

interpretations of the story of the giving of the manna in Exodus 16. According

to the biblical narrative, the Israelites were informed that they would be

issued a double ration on Friday because no manna would descend on the Sabbath.

The usual way or understanding this episode is that the double ration would

suffice for meals on both Friday and Saturday.

It is conceivable, however, that some interpreters read the story as a mandate

for eating double quantities on Friday in order to allow the people to refrain

from nourishment on the following day, in a manner analogous to the "concluding

meal" that precedes Yom Kippur.

In fact, the Torah's designation of the Day of Atonement as a "Sabbath of

Sabbaths" could be read as implying that the weekly day of rest should be

equated in all respects to Yom Kippur, and therefore should be observed also as

a fast

Talmudic tradition insisted that the requirement to eat three meals is rooted in

the words of the Torah. However, the proof text that is adduced for the practice

is rather contrived, to say the least. It is based on the fact that the word

"day" appears three times in the verse (Exodus 16:25): "And Moses said, Eat that

[i.e., the manna] today; for the day is a sabbath unto the Lord; this day ye

shall not find it in the field."

Even if we are not convinced by the midrashic attempt to squeeze three meals out

of the verse, it might nonetheless be conceded that the scriptural text contains

an explicit association between eating and the Sabbath.

We must imagine that the advocates of Shabbat fasting read the words as if they

said "eat the manna today [i.e., Friday] because tomorrow will be the Sabbath

day, when you will be unable to do so."

There are several passages in the Talmud that extol the virtues of eating three

meals on Shabbat, and consider it an expression of extraordinary piety. Rabbi

Joshua ben Levi stated in the name of Bar Kappara that those who partook of all

the required meals would be spared the torments of the "birth-pangs of the

Messiah," the judgment of Gehenna and the apocalyptic war of Gog and Magog.

Other teachers promised unlimited boundaries, or immunity from subjection to

foreign nations.

If eating three meals on Shabbat were a clear-cut precept from the Torah, it is

difficult to imagine why so many of the sages described it as an act of unusual

devotion that warranted special pride, or even supernatural rewards. For this

reason, Rabbi Jacob Tam deduced in the Tosafot that the practice of eating three

meals must not have been well entrenched during the talmudic era.

The prophet Isaiah's injunction to "call the sabbath a delight" does not strike

us initially as congruent with total abstention from eating. However, we must

acknowledge that different people find delight in different activities. Though

conventional Jewish tradition equated delight with eating and drinking, there

have always been individuals whose preference is for more spiritual or

intellectual gratification.

Indeed, to judge from the accounts by the first-century Jewish writers Philo

Judaeus of Alexandria and Josephus Flavius, the Jewish populace spent the

seventh day assembled in the synagogues for meditation and philosophical

instruction.

From all of this evidence emerges an ambiguous picture of the ideal Shabbat. The

opposing positions were epitomized in the Jerusalem Talmud in the contrasting

views of two third-century rabbis. One declared: "The festivals and Sabbaths

were given to Israel purely for the sake of eating and drinking"; while the

other insisted "The festivals and Sabbaths were given to Israel purely for the

sake of Torah study."

For the most part, Jewish tradition strove to arrive at a middle ground between

those extremes. Some sources made a distinction between the practices of

scholars, who spent the week in study and therefore needed physical relaxation

on the Sabbath, and normal working folk for whom the Sabbath provided the only

opportunity to indulge their spiritual needs.

The most widespread compromise solution was to divide the day equally between

physical and sacred pursuits, spending half a day in prayer and study, and the

other half in eating and repose.

The advocates of the foodless day of rest have long since been swept to the

margins of our tradition. Nevertheless, in our weight-conscious society there

might yet be a market that will be attracted by the prospect of a non-fattening

Sabbath.

First Publication:

The Jewish Free Press, Calgary, October 31, 2002, pp 10-11.

Bibliography:

Gilat, Yitzhak D. "On Fasting on the Sabbath," Tarbiz 52, no. 1 (1982): 1-15.

Goldenberg, Robert. "The Jewish Sabbath in the Roman World up to the Time of

Constantine the Great." In Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt, ed.

Wolfgang Haase, 2.19.1, 414-47. Berlin and New York: Walter De Gruyter, 1979.

Mann, Jacob. "The Observance of the Sabbath and the Festivals in the First Two

Centuries of the Current Era, according to Philo, Josephus, the New Testament

and the Rabbinic Tradition," Jewish Review 4, no. 22-3 (1914): 433-56, 498-532

Stern, Menahem. Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism Publications of the

Israel Academy of Sciences: Section of Humanities. Jerusalem: The Israel Academy

of Sciences and Humanities, 1980.

Urbach, Ephraim E. "Ascesis and Suffering in Talmudic and Midrashic Sources." In

Yitzhak F. Baer Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday, ed.

S. W. Baron, B.Dinur, S. Ettinger and I. Halpern, 48-68. Jerusalem: Ha-Hevrah

ha-Historit ha-Israelit, 1960.

http://www.ucalgary.ca/~elsegal/Shok...bbathFast.html

Thoughts on the article:

I find particularly useful is the

basis in the Talmud for eating three meals on the Sabbath and the proposed

counter arguments of the fasting advocates. It occured to me that the fasting

advocates could make an argument not mentioned by Segal. It would be conceeded

that 3x day mention means three occassions for eating, but that the manna

precept only says to eat that day, and therefore if they ate at only one eating

occassion they would fulfill the precept. Therefore they justified fasting the

other two, and with piety said, "I fast twice the Sabbath" (Luke 18:12).

Secondly, the Greek word δις also means "double" and "doubly". Exodus 16:29 says

bread for two days יומים . (dual) which according to Segal which double portion

they argued was eaten in advance of the Sabbath. The idea of "two" or "double"

then was taken to mean they should skip two of the three eating occassions.

Segal as formidable experience in Jewish traditional literature, and the education to prove it. I would say that his findings tip the balance toward the literal "I fast twice the Sabbath" (Luke 18:12) and away from the need to emend the text or suppose that their was a translational misunderstanding of a lamed by a Greek scribe. In other words they allow the words to make sense the way they stand, and according to linguistic conservation, when words make sense in the primary meanings, less probable senses should be avoided.